Christmas and New Year in Georgia

In Georgia, the winter holiday season unfolds in an unusual order: New Year’s Eve comes before Christmas. While much of the Western world celebrates Christmas on December 25, Georgians observe it on January 7, following the Julian calendar used by the Georgian Orthodox Church. The New Year, however, aligns with the Gregorian calendar and is celebrated alongside the rest of the world. As a result, the Georgian winter holidays stretch across multiple dates, creating an extended period of celebration that continues until January 13—the New Year’s Eve according to the Julian calendar.

During the Soviet era, religious celebrations were either restricted or kept low-key. Many festive customs, such as decorating trees, exchanging gifts, enjoying special foods, and the visit of Father Snow, were therefore transferred to New Year’s Eve. Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, this dual structure of a secular New Year and a religious Christmas remained popular. Consequently, Georgian Christmas today is primarily spiritual and culturally rooted, rather than commercial. The shopping frenzy, parties, endless feasts and dinners, and general holiday bustle typical of Western Christmas celebrations are instead associated with New Year’s Eve in Georgia.

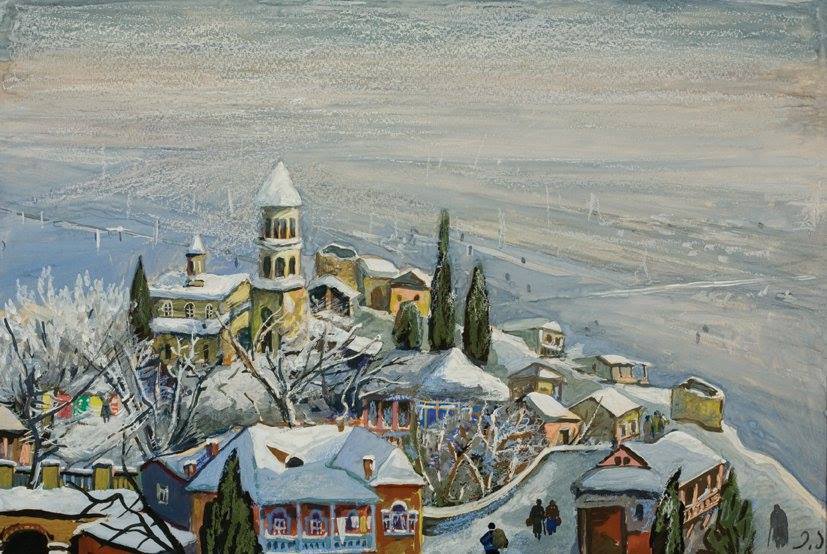

- Elene Akhvlediani – “WInter”

For most Georgians, Christmas is above all a religious occasion. In the weeks leading up to January 7, Orthodox believers often observe a fasting period, abstaining from meat and dairy. Those who strictly follow the fast usually skip New Year’s festivities altogether.

Alilo: A Festive Christmas Procession

Since the major social celebrations take place around December 31 and January 1, the festive spirit of Christmas itself is centered on church services and religious rituals. One of the most distinctive traditions is the Alilo procession, held on January 7. The word “Alilo” derives from “Alleluia” and echoes ancient hymns of praise.

- Nino Peradze – “Alilo”

Similar to caroling in Western cultures, Alilo is a joyful procession filled with music. Participants—both children and adults—wear traditional clothing, carry crosses, icons, and Georgian flags, and sing Christmas hymns as they move through streets and neighborhoods. The procession typically begins after the Christmas liturgy and concludes at a major church or cathedral.

Candle in the Window

On Christmas Eve, cities take on a warm, festive atmosphere as families place a lit candle in their windows after dark. This relatively modern custom symbolizes inviting the light of Christ into one’s home and heart, reflecting the spiritual warmth associated with the Nativity.

Chichilaki: The Georgian Christmas Tree

During the winter holidays, Georgia’s streets are filled with the vendors that sell distinctive white, curly -haired wooden “trees” known as chichilaki. Traditionally carved from hazelnut or walnut branches, chichilaki require patience and craftsmanship and are often handmade, especially in rural areas. They are decorated with fruits, nuts, and candies, symbolizing fertility, abundance, and generosity rather than material wealth or luxury.

- Elene Akhvlediani – “WInter in SIghnaghi”

Similar to many Western Christmas traditions that are originally rooted in pre-Christian pagan beliefs, such as displaying evergreens and decorating them with seasonal fruits, like apples (later turned into round glass ornaments we put on our Christmas trees today), the ritual of chichilaki goes back to the pagan times as well, when people followed nature-based beliefs and used seasonal treats to symbolize abundance. Ancient Georgians strongly revered trees, which were seen as symbols of life, renewal, and fertility. Winter, as the “death” of nature, was believed to require rituals that encouraged rebirth and prosperity in the coming year. These trees were believed to hold protective powers and to safeguard households during the harsh winter months.

With the adoption of Christianity in the 4th century, this tradition was reinterpreted rather than abandoned. Chichilaki became associated with Christian symbolism and the Nativity, representing purity, spiritual light, the Tree of Life, and even the beard of St. Basil the Great, a saint linked to generosity and blessings. Though especially common in western regions such as Guria and Samegrelo, chichilaki are now widespread throughout the country.

A key aspect of the tradition occurs after Christmas. On January 19, Epiphany, families traditionally burn the chichilaki, symbolizing purification, the release of misfortune, and hope for renewal in the year ahead.

Additionally, chichilaki is often considered an eco-friendly alternative to plastic Christmas trees, as it is carved from natural wood and provides the option of either safely discarding it or keeping it for years to come.

First Footing: Mekvle and Visiting Customs

Among many Georgians, particularly in rural areas, the first guest to enter a home on Christmas or New Year’s or Christmas Day is called a mekvle. This guest is considered a harbinger of fortune and good luck; upon entering, they throw candies and offer blessings to the family. Only after mekvle arrives do festivities formally begin. Some folks take mekvle tradition seriously and invite a particular person to be their mekvle, as they will bring good luck, and it is a role that cannot be taken lightly.

- Nino Peradze – “Alilo”

Anyone can accidentally become a mekvle, so when we leave the house on New Year’s Eve or Christmas to visit our loved ones, we stuff our pockets with candies and distribute them everywhere we go. Some people try to be especially considerate to everyone, often giving candy to taxi drivers or night shift clerks in the store.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year

We created Memo — a brand where Georgian memories come to life.

Visit Memo By GSH and take a piece of Georgia with you – Www.memories.ge